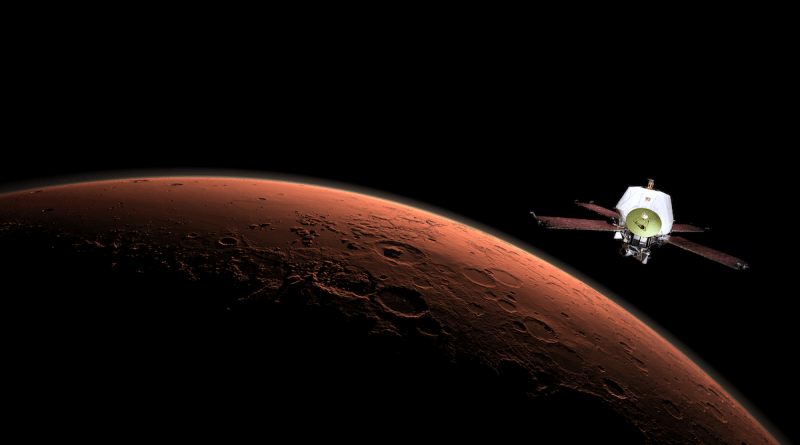

50 years on Mars

[ad_1]

One of the mission’s more puzzling discoveries was that the planet’s surface temperature was significantly lower when the atmosphere was dustier. Among those who pored over these measurements were Mariner 9 team members Carl Sagan and his first graduate student Jim Pollack, an expert in planetary atmospheres. They and others would combine Mariner 9 data with surface data gathered a few years later by the Viking landers — as well as data on Earth’s surface temperatures after large volcanic eruptions — to develop models that explained how dust suspended in a planet’s atmosphere cool the surface while simultaneously warming the upper atmosphere.

Sagan and his colleagues eventually used these models to predict that a global nuclear war between the superpowers on Earth would result in a nuclear winter — a massive cooling of our planet’s surface. Clearly, understanding our neighboring planets like Mars can prove to be more than just academic.

Mars emerges

The dust finally began to clear from the martian atmosphere in early 1972, allowing Mariner 9 to begin systematically mapping the entire surface of Mars. Planetary scientist and space artist William K. Hartmann, then a young member of the Mariner 9 science team, recalled how shortly after the spacecraft arrived, everything was completely obscured by dust except for the four mysterious dark spots near the equator:

“One day, Carl Sagan came running down to the science team room from the upstairs ‘computer’ room that had been receiving images from the Goldstone tracking antenna, waving a Polaroid photo of the TV screen (the mode of initial transfer of Mariner 9 images to the science team!). The photo revealed a pretty clear volcanic caldera in a summit protruding from the clouds. That was the day that everyone realized the dark spots were enormous shield volcanoes.”

Shield volcanoes are common geologic features on Earth; among the most famous are the Hawaiian volcanoes Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. The volcanic structures discovered on Mars, however, make even Earth’s largest examples seem puny by comparison. The largest martian volcano, comparable in area to the state of Arizona but towering some 82,000 feet (25 kilometers) above the nearby plains, was named Olympus Mons because it coincided with the perennially cloudy region that 19th century Mars observer Giovanni Schiaparelli had dubbed Nix Olympica, the Snows of Olympus. The three other dusky spots corresponded to the shield volcanoes now known as Ascraeus Mons, Pavonis Mons, and Arsia Mons, from north to south.

[ad_2]

Original Post

653 thoughts on “50 years on Mars”